Day 9: Mean Tones and Split Keys

by Chris Porter

The 1992 Brombaugh organ in Haga Church, Göteborg, Sweden.

After two mornings of sleeping in (that’s what weekends are for, right?) we met for a relatively early (9 am) appointment at the Haga church of the Church of Sweden in central Gothenburg. The organist, Ulrike Heider, gave us a brief demonstration of the church’s two organs before leaving us to spend the morning exploring them on our own. Uncharacteristically, we spent most of the time on the newer and smaller organ. This extremely interesting instrument was a small, historically-inspired organ in the north German Baroque style, complete with mean-tone temperament, split-key accidentals, and an option for hand-pumped bellows (which the group enthusiastically set to pumping). Perhaps even more surprisingly, this 1992 instrument was built by an American builder, John Brombaugh, of Portland, Oregon. We enjoyed playing Sweelinck and Buxtehude on this finely crafted instrument.

Brandon Santini at the 1861 Marcussen organ in Haga Church, Göteborg, Sweden.

We also spent a brief time on the church’s large organ, an 1861 instrument by the Danish firm Marcussen & Søn. After two rebuilds introducing pneumatic and then electric action, it was restored to close to original condition in the early 2000’s. The instrument has a warm, rich sound, with many blending stops on which to create gradual crescendos or decrescendos.

The 2000 GoART research organ in Örgryte New Church, Göteborg, Sweden.

The generally pleasant weather had turned cool and damp, and we found ourselves exiting the church into light showers. After a quick lunch at a nearby café, we hailed rides to Örgryte New Church, where we were to spend the afternoon playing a true-to-original reconstruction of a Schnitger organ, modeled on the one we had visited at St. Jakobi in Hamburg just a few days earlier (see Day 6).

Hans Davidsson points out features of the North German Baroque organ in Göteborg.

Here we met Hans Davidsson, who had given the concert we enjoyed Saturday at the Dom Church. Ebullient and enthusiastic, Hans gave us the fascinating history of this instrument. Attending an Organ Historical Society conference in Arizona in 1992, he was inspired by the inquisitive and collaborative efforts by American organ builders and historians to re-create the sounds of historic instruments, through accurate reconstruction using original materials and construction techniques. This led ultimately to the idea to (re)construct the Schnitger with fully accurate historic detail, and to the formation of GoART (the Gothenburg Organ Art Center), affiliated with the University of Gothenburg, to carry out the project and to conduct other historical organ and keyboard research and construction.

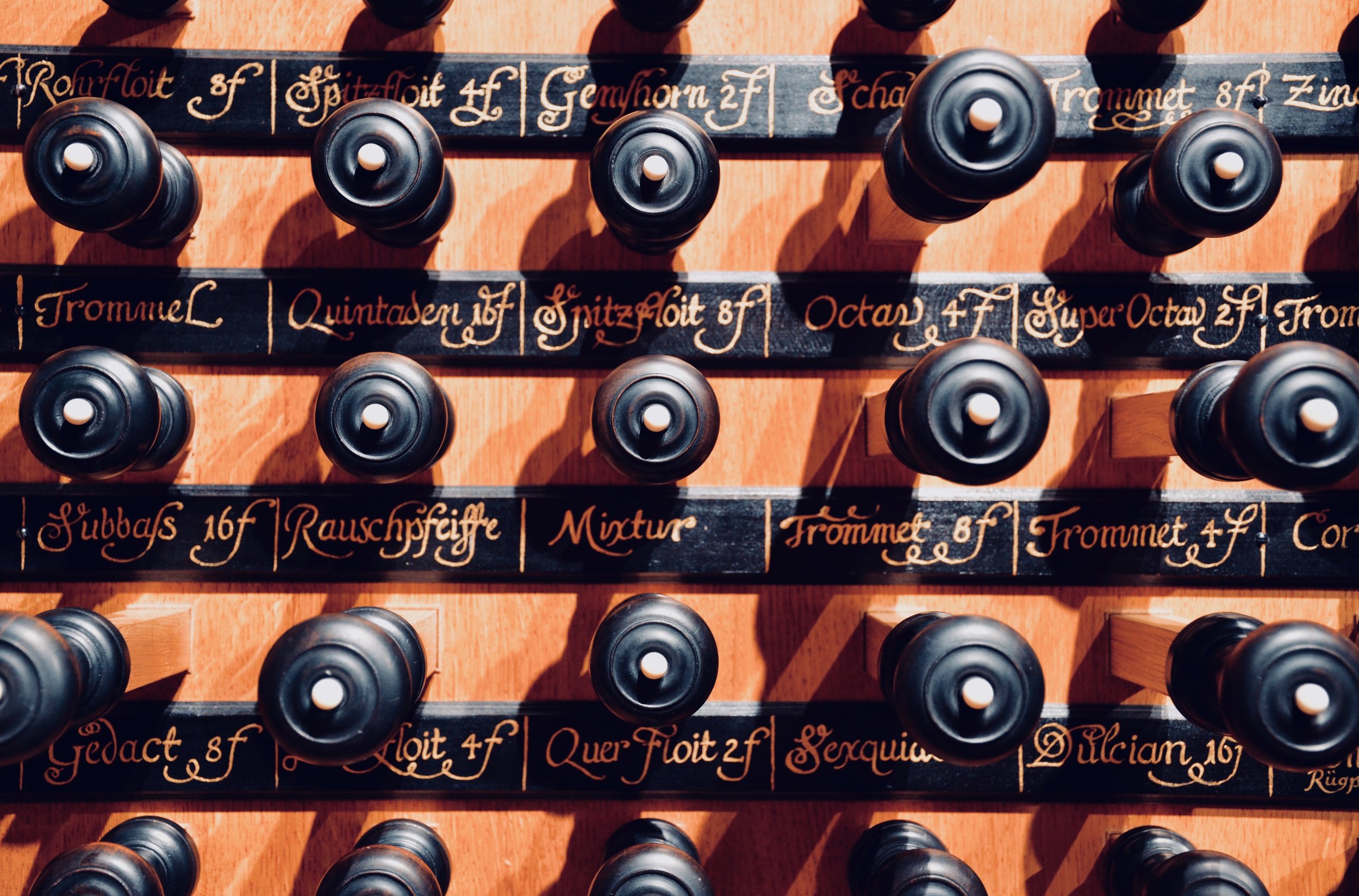

Keydesk detail, with sub-semitones, 2000 North German Baroque organ in Göteborg.

The organ is tuned in quarter-comma meantone temperament and built with split keys for sub-semitones (read further for a brief explanation) — characteristics no longer present on the St. Jakobi Schnitger. Other important details include the composition of the metal used in the pipes, which was determined from analysis of the original pipes at St. Jakobi; as well as the dimensions of the wind trunks from the bellows, which were obtained from meticulous notes taken by a 19th-century organ builder working on a (not historically accurate) renovation. The work included collaboration with materials scientists as well as fluid dynamics researchers at the local Chalmers technical university, who modeled the airflow in the wind trunks and confirmed that the small size of the trunks would be successful even though “nobody thought it would work.” The organ was inaugurated in 2000.

In addition to building the new “old” organ, the inside of the church needed to be completely renovated, with a new wood ceiling and wood floors replacing carpeting, to provide the necessary acoustics for the organ. Funding for the reconstruction project was obtained from a variety of sources, including the state, which provided unemployment funds to support labor for construction on the building; the university, which paid for raw materials; grants from public and private foundations for construction of the organ; and funding from the congregation for necessary exterior repairs to the building. Hans noted that the entire effort involved nearly a dozen entities and that the American-inspired collaborative model for the work was new to European scholars. The involvement of the university (and much of the foundation funding) was justified by viewing the organ as an artistic research tool (in the same way a science lab is outfitted with necessary equipment), thus providing the necessary hardware to explore the performance of music with original sounds and mechanical operations.

Hans Davidsson coaches Adrian Cho at the 2000 North German Baroque Research Organ in Göteborg.

Our group had the entire afternoon to familiarize ourselves with the organ’s unusual keyboards, pedalboard, and sounds. For the many blog readers who are likely unfamiliar with the concept of meantone temperament, an extensive crash-course can be had on Wikipedia. Suffice to say briefly that an octave (e.g., C to c) must be divided into twelve intervals (semitones) and it is not possible to optimize the distance between all intervals. Today’s most common tuning system is “equal temperament,” which tempers all intervals (except octave) equally and therefore minimizes dissonances. The downside is that none of thsee intervals are trule “pure” and “in-tune.” Meantone is an older tuning system, prevalent in the 17thcentury, that creates pure thirds at the expense of certain other intervals — especially in less common keys. Accidentals that are the same in our modern temperaments (e.g., G# and Ab) are different in this type of temperament, and therefore require split “black” keys — one of which plays G# and the other of which plays Ab. It took some practice for us to find the correct accidental. Also requiring some adjustment was the shortened keyboards and pedalboard, which substituted lesser-used notes at the low end of the scale (e.g., C# and D#) with more common notes in order to save on material and construction costs.

Hans very generously spent the afternoon coaching us as we attempted to play Buxtehude, Weckmann, Sweelinck, and other composers whose works would have been played on meantone organs. He encouraged me to use time to emphasize the unusual contrasts created between progressions from more dissonant to consonant intervals that are characteristic of meantone performance.

Brandon Santini at the console of the 1871 Willis organ in Göteborg, Sweden.

After more than five hours with this instrument, our group took a brief look at the church’s other organ, an 1871 Willis that had been moved from England — first to the Netherlands in 1971, and then to Gothenburg in 1998. The largest Victorian organ of British manufacture in Sweden (and also a very fine instrument!), couldn’t keep us around long, though, as it was now after 7 pm the group decided that it was time for dinner. We retreated to our loding for an extremely colorful buffet of stuffed peppers prepared by Brandon.